Thousands of intrepid stewardesses, nurses and nannies chose careers on board the enormous ocean liners then sailing across the North Atlantic. In an era before it was possible to fly between continents, a six or seven day voyage aboard one of these vast ships was the only feasible way to travel the world’s oceans. Shipping companies like Cunard and White Star Line needed able and competent female employees to assist their women passengers of all kinds, from the celebrities, film stars and millionairesses in first class, to the performers, writers and businesswomen in second class, right down to the migrants and refugees below decks in steerage, who were seeking new lives in the New World.

Resourceful and self-reliant, these mould-breaking professional seawomen withstood winter storms, shipwrecks, icebergs, seasickness, Prohibition, enemy torpedoes and occasional sexual harassment from their male colleagues and amorous passengers, in pursuit of respectable, rewarding and interesting careers aboard the glamorous ‘ocean greyhounds’.

The unsinkable stewardess

The defender of virtue

The courageous engineer

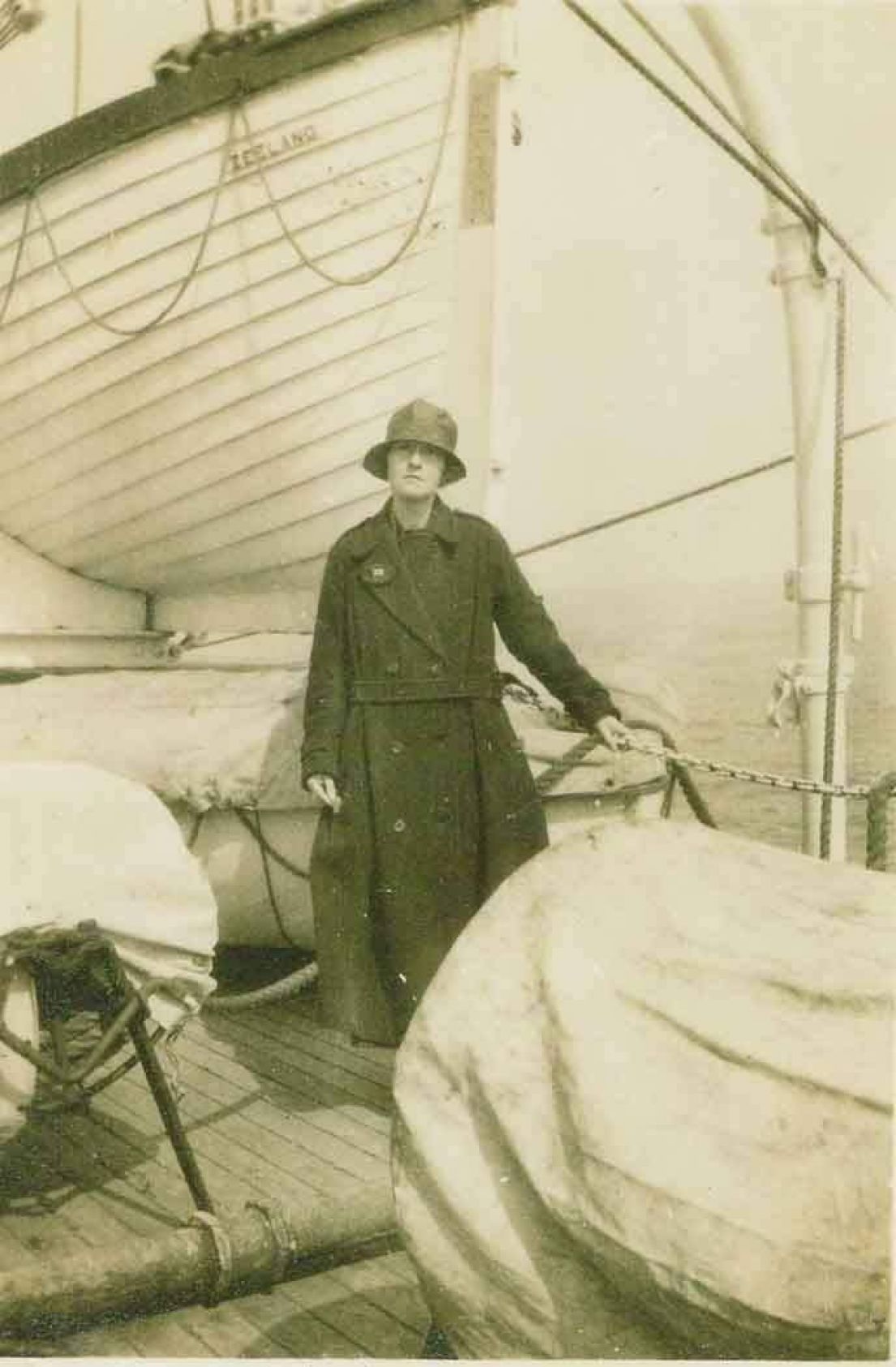

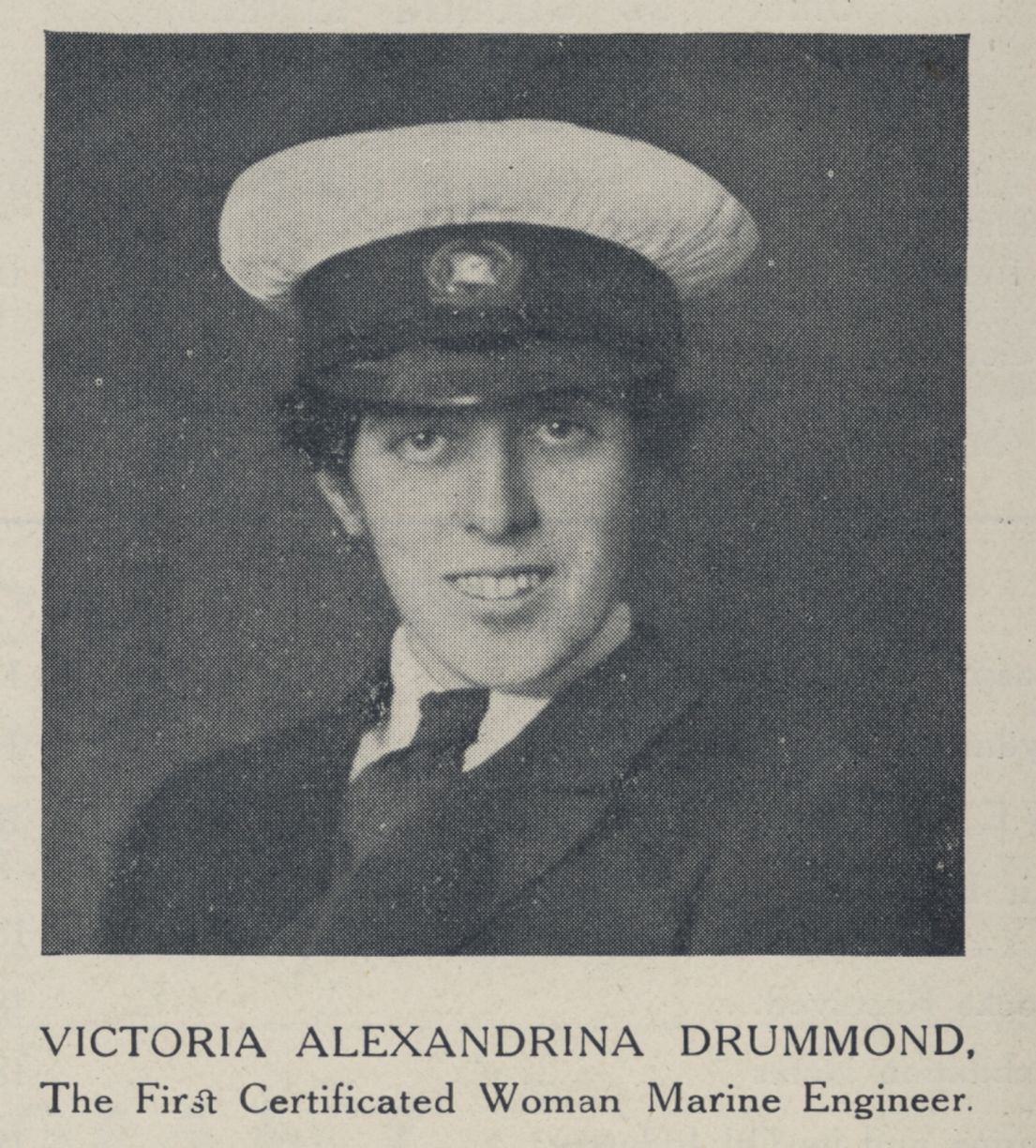

Edith’s own heroine was a fellow female seafarer, Victoria Drummond, who withstood fierce prejudice to take on a career previously only open to men. Edith wrote in her memoirs of Victoria “Her record is fantastic – forty years at sea. Yet the young engineers who served in my ships opined that she was crackers – had she joined us, she would have been in for a rough time.” Victoria Drummond qualified in the 1920s as the world’s first woman marine engineer, and for decades she worked on ships with all-male officers and crew. She came from a more privileged background than most; her godmother was Queen Victoria, and her family whole-heartedly supported her unorthodox choice of career.

Find out more

- Read more about these pioneering seafarers and their many intrepid contemporaries in Maiden Voyages: Women and the Golden Age of Transatlantic Travel, by Siân Evans, published by Two Roads

- Blog - Search for more stories of Extraordinary Women