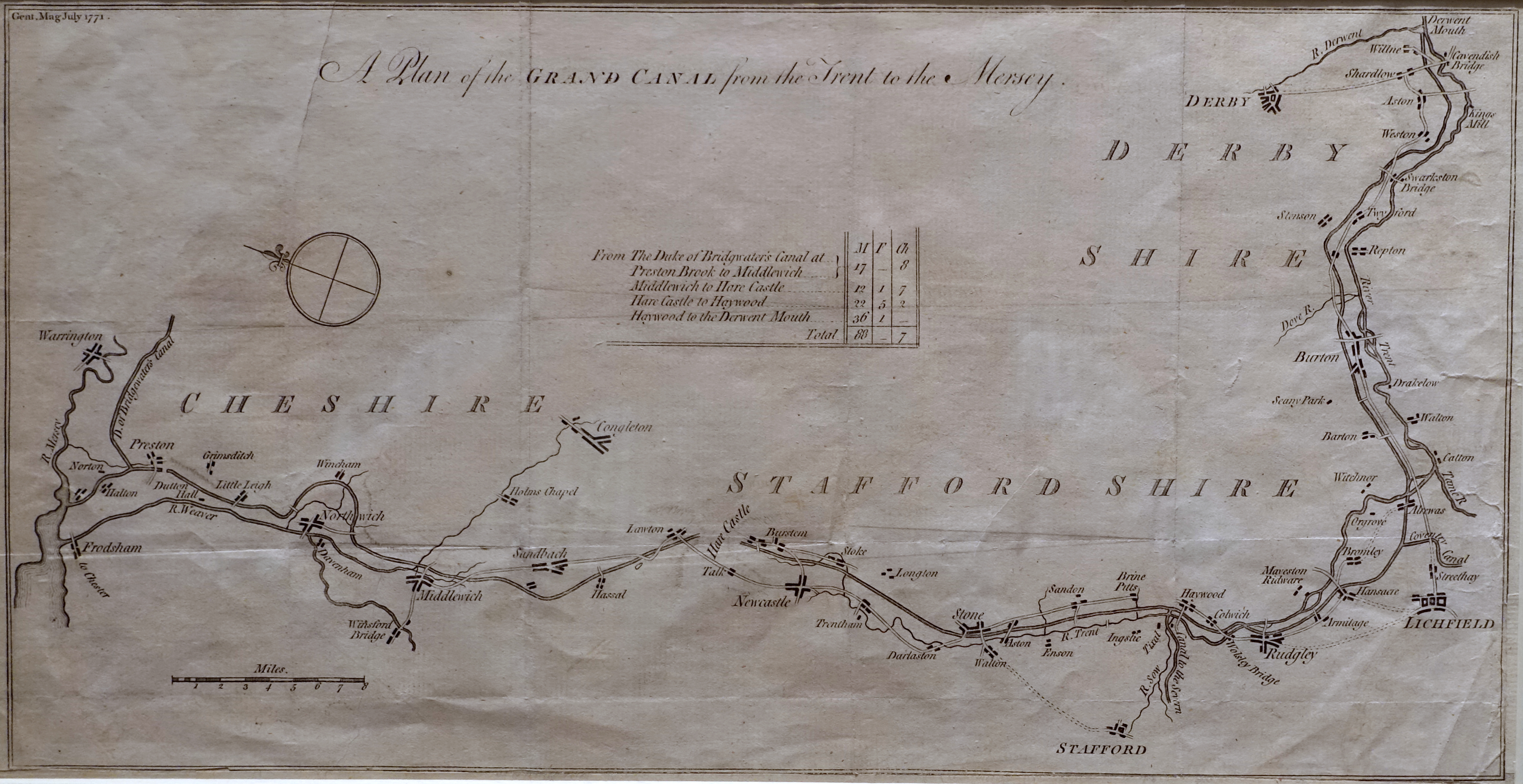

A plan of the Grand Canal from the Trent to the Mersey, in The Gentleman's Magazine, July 1771. Preston Brook is at the far left.

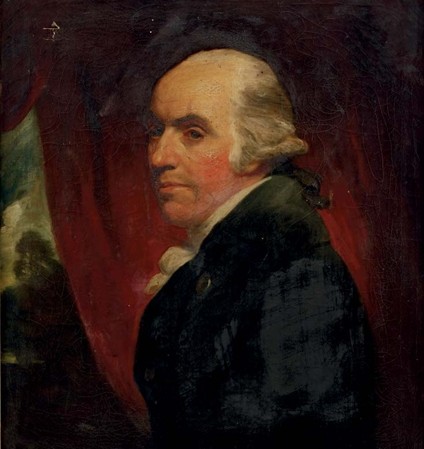

The year is 1768, and this is George Heron of Daresbury Hall in Cheshire, one of the most interesting men that you’ve never heard of! The urgent missive he needs to reply to is another letter from his brother-in-law bemoaning the oncoming Bridgewater canal. George was not a massive fan of the canal. He and his in-laws were firmly on the team of the existing river navigations of the Weaver and the Mersey and Irwell, and they had all spent vast efforts trying to stop the Duke of Bridgewater from building any canal at all, and then more effort trying to stop him from joining his canal to another one and therefore bypassing the existing navigations and reducing their income from them.

Canals might be the future of industry, but to many of the gentry they were a threat to their lands, their stability and, in some cases like this, their income. However, George was a practical man and he recognised it was now a lost battle, and thus had to put his considerable charisma to restraining his wife’s family from doing anything silly, like setting the dogs on the Bridgewater agents.

Getting to know George

Our research has revealed more than the basic profile details though, we ’ve also learned that…

- He had a dog named Barto and smart hunter horses for sporting events but preferred sturdy Welsh Cobs for travelling.

- While he had blue livery made for his servants for official functions, he personally seems to have preferred a smart salt-and-pepper suit for himself (and soft leather breaches for all the hours he spent in the saddle riding back and forth on business).

- He liked to go bowling, even though he sucked at it!

- He was very careful to make sure his children respected their fellow men and women, regardless of class, and signed off monies his daughters spent on trying to help educate the local children, even when they dabbled in teaching them themselves.

- He respected love, giving the lease of the local pub to two of his servants when they married and apparently stepping in when his son eloped with a local heiress to make sure that her guardian didn’t have the whole thing swept under the rug.

George’s web

But to tell his story properly, you must also tell the story of the servants in his household, the tenants on his land, the craftsmen who fitted out his house, the boatmen and sailors who carried his cargo. A thousand stories all falling back to one man. The six degrees of George Heron if you will. Here are some gems we’ve uncovered…

The stablehand

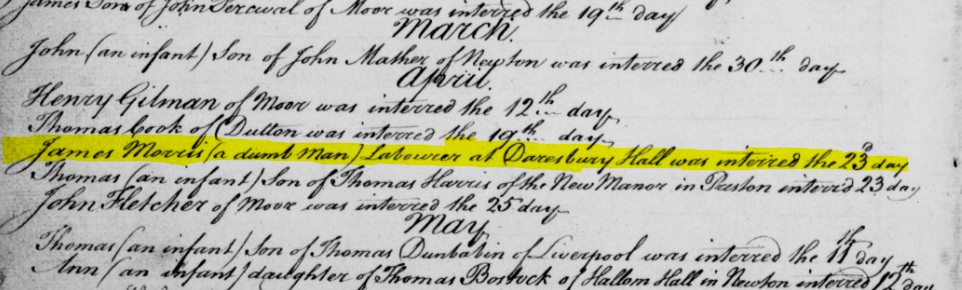

Burial record for James Morris.

James Morris was probably born about 1750 in poverty in Penketh, and regarded as “slow” from a relatively early age. He came to George through a combination of luck and charity, and despite never saying a word he proved a capable member of staff, doing whatever job was asked of him with a quiet smile.

The batman and his sister

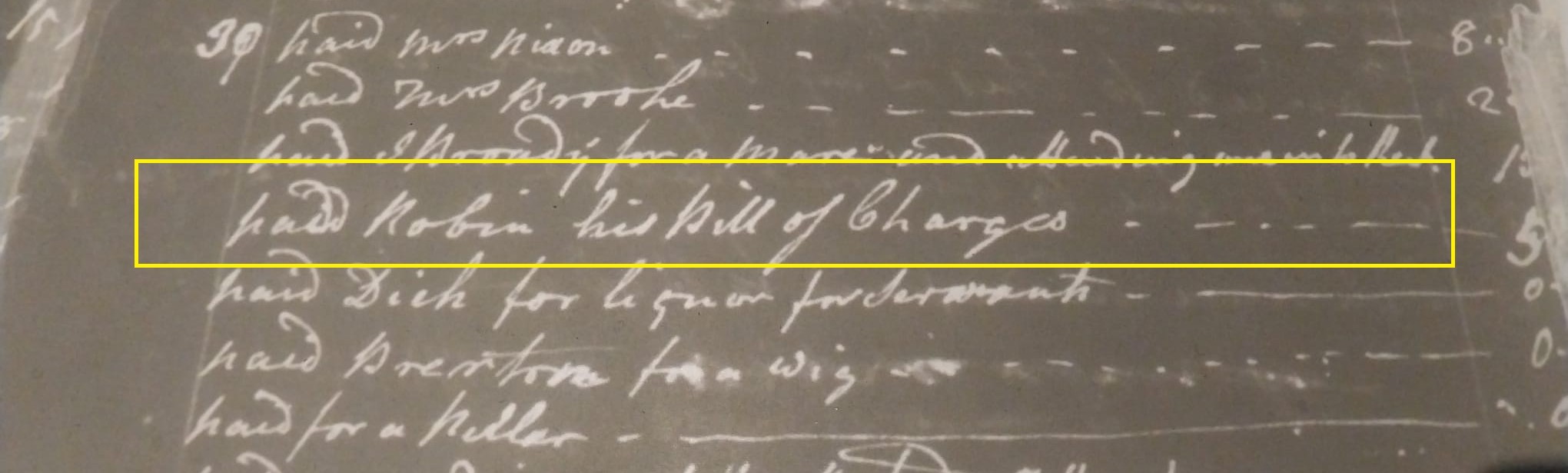

Robin Kinder was George’s ‘batman’ – a close personal servant who accompanied him all over the country. On hearing that Robin’s sister was set to be married, George quietly started having all his shirts made by her, paying double what anyone else was getting paid. As the wedding got closer, the accounts show an increase in purchase of clothes for Robin, including a petticoat! This suggests George was effectively paying for the all important wedding ‘trousseau’ to be made.

Find out more

- Heatherfield Heritage

- Heatherfield Heritage's festival case study - Read about their first year participating in Heritage Open Days.

- What's on - Keep an eye out when the event directory launches this summer for more chances to discover stories of our Everyday Histories.