Women have been involved in engineering throughout history, but their role is often hard to define and see. Lines are blurred as they worked in partnership with their husbands or as part of a family. And even when they left home and worked at research establishments they’re often uncredited - remember those scenes in the recent Hidden Figures film where NASA mathematician, Katherine Johnson, kept trying to include her name on the reports and being overwritten?!

At Heritage Open Days we hope to help highlight some of these stories throughout 2018 as part of our Extraordinary Women strand. And this week’s conference at the stunning Institute of Engineering and Technology was full of inspiration…

Taking to the AIR

Women were involved in the earliest days of aeronautics in England - The Weinling Family (including daughters, Mary Anne, Eugene, & Willie) were keepers of the secret of processing 'Goldbeaters Skin'. This was the essential tissue required to create air ships as it was impermeable to hydrogen. They worked at a balloon factory in Farnborough that later became the Royal Aircraft Establishment, which, as the world wars lost men and drove demand for aircraft, actively recruited women from universities.

Sailing the SEA

Blanche Coules Thorneycroft was the first woman to be professionally recognised as a naval architect but the true extent of her work is difficult to gauge. Working alongside her father and brother at the family firm her diaries reveal a detailed involvement in the development and testing of naval designs including the revolutionary Coastal Motor Boat. But she was rarely credited – take a look at Wikipedia’s pages on the boat and the company, she doesn’t even get a mention! (*but also see the brilliant Women in Red project Wikipedia is running to redress the balance)

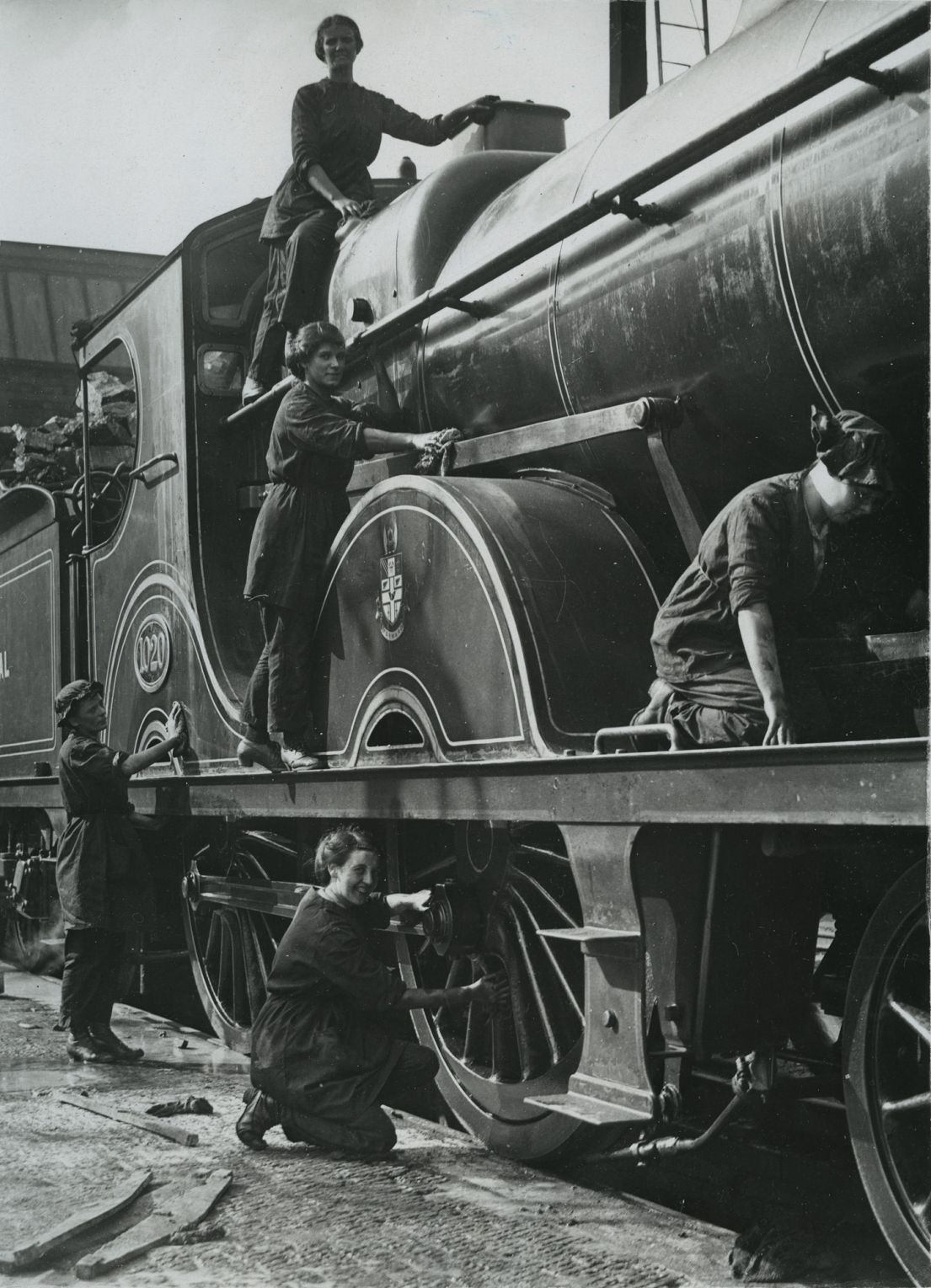

Criss-crossing the LAND

Discover more…

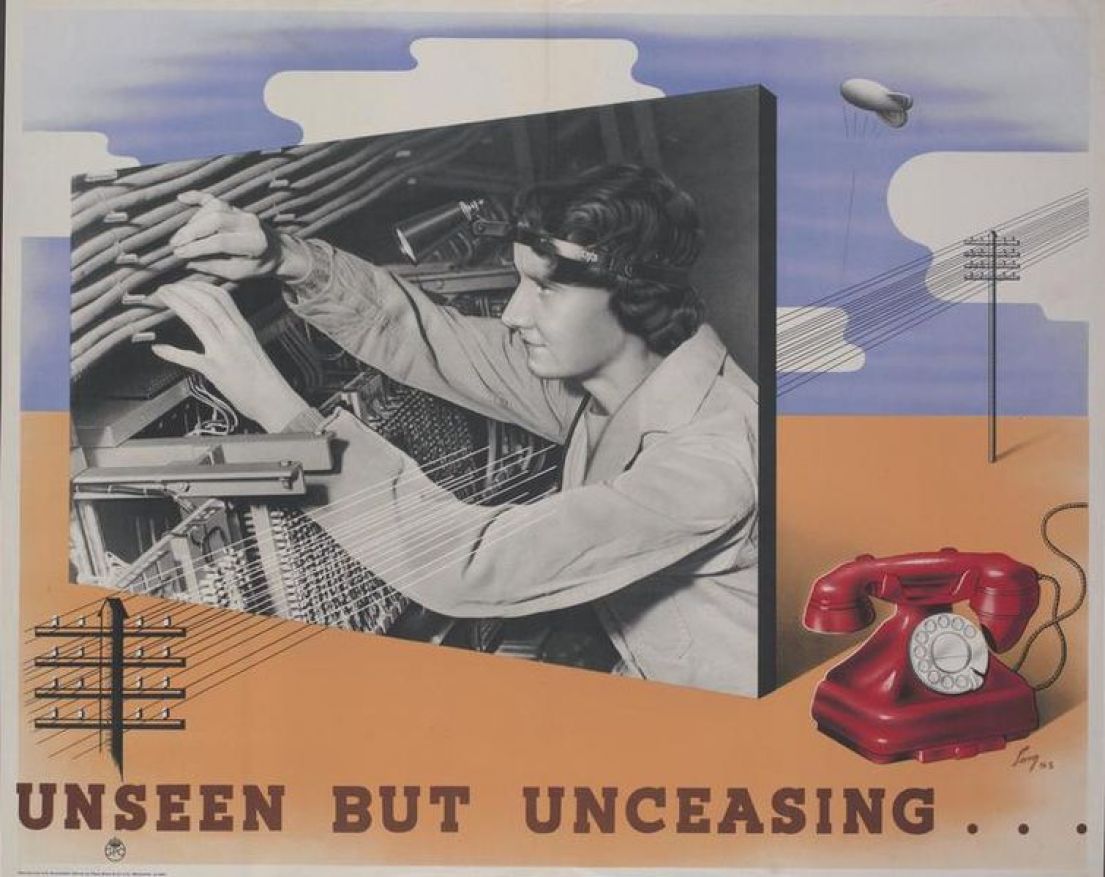

It is estimated that 1.5 million women were employed in engineering during WWII but despite the investment in their training and the demonstrable skills acquired and shown, this was all too often seen only as a ‘temporary’ emergency state. After the war the Women’s Engineering Society was set up to help combat such attitudes and ensure a lasting place for women within the sector.

Many thanks to the women (and men) who are helping to highlight the work of all these extraordinary women in engineering. Please do follow up on the links below to some of the projects mentioned at the conference – I can only give a snapshot here of their great work!