**CONTENT WARNING - references to suicide. If you are struggling, please call Samaritans free on 116 123.**

This was my first year participating in Heritage Open Days. The project was time-consuming but also rewarding, as I was learning the process and developing my approach along the way. The whole experience has been deeply meaningful and affirmed my belief that sensitive subjects, when handled with care, can bring people together rather than apart. I felt proud to see that even the quietest stories — like that of Princess Irene Duleep Singh — can find light, dignity, and resonance in the public eye.

Why I take part

What I did for HODs

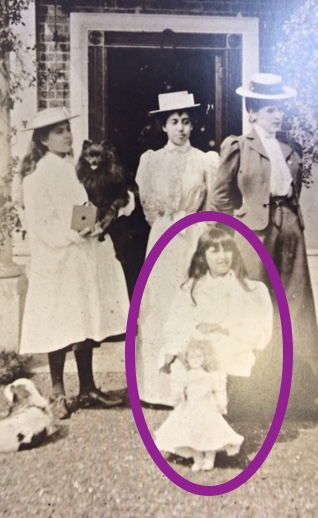

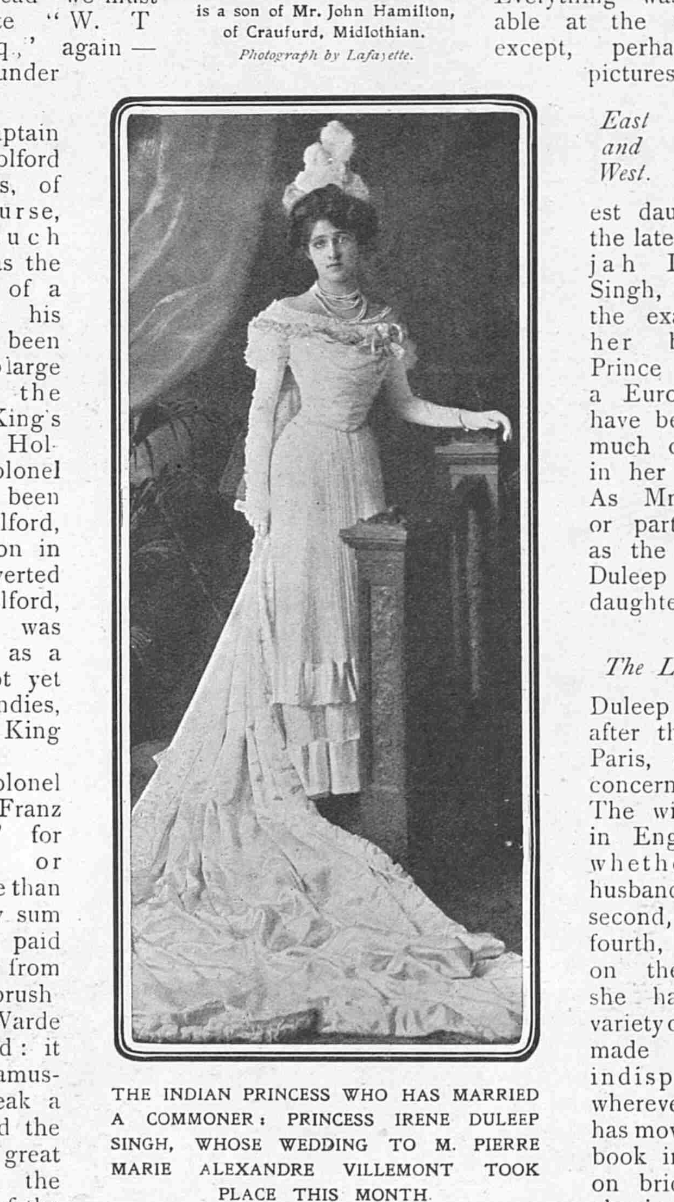

I created and delivered a series of talks on “A Forgotten Princess: Irene Duleep Singh and the Evolution of Mental Health and Law” at Erasmus Darwin House in Lichfield. The event explored Princess Irene’s life as the last born of Maharaja Duleep Singh — and the last descendant of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Sikh Empire royal line — whose family’s fate was bound up with the Koh-i-Noor diamond, now the most famous jewel in the British Crown held at the Tower of London. It examined how her struggles with mental illness reflect broader shifts in society’s understanding of women, trauma, and silence.

Working collaboratively

Your enthusiasm is infectious. I came to this event not knowing a single thing about the Sikh dynasty or the Koh-i-Noor’s background, but your talk educated me. When you complete your proposed book, I’ll be one of the first to buy a copy. Keep up the excellent work.

Best bits

One of my most powerful realisations was that this heritage event functioned almost like a bereavement and therapeutic space — a moment of collective reflection that helped broker peace. Princess Irene’s story — as the last-born of that royal line who died by suicide — allowed audiences to connect emotionally with the sense of loss, disinheritance, and remembrance. Opposite Erasmus Darwin House stands Lichfield Cathedral, where the Anglo-Sikh War Memorial — and the once-displayed Sikh battle standards — still seem to echo the memory of Punjab’s annexation. That proximity felt symbolic — as if the story had come full circle, from empire and exile to understanding and unity. It became a space where the pain could be held and explored with care, not suppressed or denied. For me, it affirmed the potential of shared heritage to bring communities together in empathy and care, not division.

Overcoming challenges

Maximising accessibility

Navigating copyright

Sundeep’s Top Tips

1. Invest in marketing: It can be a challenge, but it’s worth it — from creating eye-catching leaflets and posters to using targeted social-media adverts.

2. Reach out to the press: Contact the local press, but also try national outlets. Heritage Open Days is a national event, and if you’re offering something online, national coverage can be just as relevant as local.

3. Offer refreshments: Providing tea, coffee, or small treats at in-person events helps create a warm, welcoming atmosphere where people feel comfortable to stay and talk.

4. Choose the right venue: Ideally, find somewhere that’s already a heritage setting to create atmosphere — but make sure it’s accessible, with parking or good public-transport links so everyone can take part.

5. Be rigorous and meticulous with images and copyright: Always check the status of any image you plan to use. Wikimedia Commons is a helpful source for public-domain and freely licensed material, but you’re still responsible for verifying the licence and its provenance. Remember: owning a physical original does not confer copyright in the image. If the underlying work is in the public domain, buying or possessing a print does not revive copyright (though contractual terms on a specific copy may restrict how you use that copy). In the UK, duration depends on the type of work and when it was created or published, with special rules for older photographs, newspapers’ typographical arrangement rights (25 years), Crown/Parliamentary works, and some unpublished works protected until 2039. The “pre-1945” guideline can be a useful first screen for many historical photographs and press images, but it’s only a heuristic — always confirm the creator and dates before treating an image as public domain.

6. Protect access to heritage: Safeguarding the public domain and ensuring open access isn’t just a legal responsibility — it’s part of protecting heritage itself.

Images from: HODs 2025 - Trevor Ray Hart

Inspired?! Find out more…

- Samaritans – If you are struggling, please call Samaritans free on 116 123.

- Follow Sundeep Braich on Instagram – Follow Sundeep for the latest news of her research.

- More case studies - Meet other local organisers

- Get involved - Taking part in Heritage Open Days