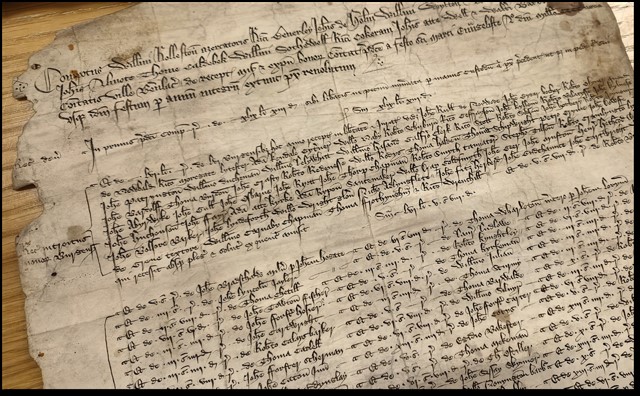

An illustration of brickmaking from the mid 15th century (British Library Add MS 38122. Wikimedia Commons).

Humble building blocks

Bricks are all around us, everywhere we look. Despite the increased use of concrete and cement in construction, most new houses are built with bricks, on average requiring 8,000 each. These small, mostly red, rectangular blocks of cooked mud enclose our houses, our gardens, our workplaces, and our government buildings. They can even be found under our feet. Look closely: bricks are amazing.

Spot the difference

Building a bar for £96.17s 4½d

Most old English towns had a bar or gate to control access. Beverley’s North Bar, built between 1409 and 1410, is England’s oldest brick gate. It was designed for toll-collecting, rudimentary defence, and as a status symbol. Toll collectors, using the seats built inside the bar, took money from traders visiting the markets, and for security there was a portcullis gate and huge wooden doors. Although the traffic through the bar now consists mostly of cars and bicycles, in the past 600 years many millions of people have passed through its arch: kings and queens, princes and gentry, on horseback, in stagecoaches and carriages. Commoners have come and gone on foot, bringing all kinds of goods: cattle, sheep, hens, beer, butter and eggs.

Beverley's North Bar - Built to guard the road out of town, inside you can still see three niches for the toll collectors' seats, its huge wooden door and portcullis slot to close the gate as needed. (Images courtesy of Kloskk Tyrer)

Medieval planning permission

Construction of the new bar was organised by the merchant and councillor William Rolleston, assisted by the Masters and men of the town guilds. As was typical in medieval England, the employer (the council) paid for workers and materials directly, without any intermediary. There is no mention in the accounts of architects, surveyors, drawings, estimates or contracts, but there was a planning meeting, where a team sent by the archbishop of York, in the Middle Ages the lord of Beverley, viewed the site and accepted the council’s proposal. The bar was built in nine months and cost £96.17s 4½d, of which roughly half was spent on materials, half on labour and transport.

Bricks, tiles and ‘squynchons’

We know how the North Bar was constructed, as every payment made was recorded by the council on a roll of parchment nine feet long. This rare, ancient and very detailed document is in the town archives. It reveals that the bar required 113,200 bricks, although in 1410 ‘bricks’ were not yet known by their Dutch-derived name, but were called wall tiles, thack tiles (after ‘thatch’) for roofs, and squynchons (meaning squint or oddly shaped tiles).

The bricks were made two miles away, with mud sourced from the River Hull’s banks, and brought by horse-drawn cart or sled to the building site. Twenty different suppliers are named, including John Mudfysch, William Potter, Agnes Tiler (the only woman brickmaker) and William Rolleston, who provided 34,000 bricks. The going rate for North Bar bricks was generally 3s 8d per thousand, and these were laid in a pattern that is best described as ‘Loose English Bond’ or ‘Irregular’.

The mortar that bound the bricks was sand and burnt lime supplied by Adam Lymbirner (pronounced ‘lime burner'): the places where lime was quarried and processed are still known in the town as ‘Limekiln Pits’. Fifteen other trades were involved, including carpenters, sawyers, smiths, plumbers, nail-makers, a locksmith, carters and numerous bricklayers, paid about 6d a day, while their labourers received 4d. They worked all daylight hours, six days a week.

If the bar was built today

These days the construction of such a major project would proceed very differently. The accounts would be in English and not Latin; printed on paper instead of written on parchment by hand. Working conditions would be safer and the labour largely mechanised. There would be architects (this profession did not exist in England in 1409) and surveyors, drawings and contractors. The speed of construction, too, would be very different. The council was granted planning permission for the bar in July 1409, and in April 1410 this magnificent structure was completed, its great doors fitted and varnished. It would take very much longer than nine months to create such a building today.

Find out more

- Nathaniel Lloyd, A History of English Brickwork (1925) – a classic available from the Internet Archive

- Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘The Buildings of England’ series – introductions in these books discuss building materials

- Alec Clifton-Taylor, The Pattern of English Building (1965)

Heritage Open Days 2025:

This year we're exploring how we've built and designed the world around us.

- Festival theme: Architecture - Check out our theme pack for ideas and resources.

- Event directory - Search our listings from 2 June, there's a filter for 'architecture' themed offers!