Jane Austen (1775-1817) was one of Hampshire’s most famous working women, gaining a small amount of valued financial independence from her writing. Her novels continue to inspire and amuse millions of people today, featuring well-loved heroines like Elizabeth Bennet and Emma Woodhouse. Less often noticed or remembered though are the women in working roles who are incidental characters in her stories.

Hampshire Cultural Trust’s special exhibition to mark Jane Austen 250 explores these lives lived in the background. Without women workers, the bustling towns of Highbury and Sanditon and the prosperous houses where Austen’s stories are set, could not function. The exhibition reveals the precarious lives of real working women from Austen’s Hampshire, drawing out the parallels between fact and fiction.

Here are three examples of the stories to be explored…

Domestic Service: The housekeeper

The housekeeper came; a respectable-looking woman, much less fine, and more civil than she had any notion of finding her…

The majority of working women in Austen’s novels are domestic servants. This was the most common form of employment for women during the Regency period. The housekeeper was the senior female servant in a household, supervising all of the other women servants. She would work closely with her employers to plan and manage provisions, hospitality, clothing, cleaning and laundry. Often a housekeeper would be unmarried or a widow, but on occasion she might be part of a working couple with the senior male servant.

Real-life Hampshire housekeeper Mary Lunn was born in 1777 in Crondall, the eldest of eight children. In around 1805 she went to work as a lady’s maid for Mrs Eliza Jervoise, at Herriard Park, not far from Basingstoke. Mary did well, and in 1810 she was promoted to housekeeper. In 1813, Mary married the Herriard butler, George Mountford. The birth of a son, John, was certified on 2 December, 1813, recording his ‘abode’ as a temporary stay with Mary’s widowed mother in Basingstoke. Records at Hampshire Archives include receipts for expenses and wages for a temporary housekeeper at Herriard for around a year from September 1813. Mary then returned to her duties for some years. She was recorded still living in the Herriard parish in the 1841 census. A burial record of 1857 seems a likely match for Mary, which would mean she lived to be about 80.

Education & Childcare: The governess

The plan was that she should be brought up for educating others; the very few hundred pounds which she inherited from her father making independence impossible … by giving her an education, he hoped to be supplying the means of respectable subsistence hereafter.

It was a widely held view in Austen’s time that women were naturally suited to such work. A governess would come from a genteel family and, like Jane Fairfax, have education, accomplishments and manners but not the financial means to live independently. By taking a position in a well-off household to teach children and mentor young women, she gained shelter and a respectable living. The prospect of becoming a teacher or governess hangs over several of Austen’s characters as an unappealing fate. The status of a governess could be difficult — neither one of the domestic servants, nor entirely part of the family.

When Emma, with its many references to governesses, was published, Austen sent an author’s copy to her friend Anne Sharp. Anne was governess to Edward Austen’s large family at Godmersham, Kent, from 1804 to 1806. She and Austen became life-long correspondents. Anne suffered ill-health, and left to look after one little girl for a Mrs Raikes. Even this proved too much and she became companion to Mrs Raikes’ disabled sister, Miss Bailey. Anne then left Miss Bailey in Summer 1811, to become governess to the four young daughters of a widow, Lady Pilkington. She may have seen Jane that year. She certainly visited Chawton in June 1815. By 1823, Anne had her own boarding-school for girls at 14-15 Everton Terrace, Liverpool. She retired to York Terrace, Everton in 1841, and died on 8 January 1853.

Trade: The milliner

Look here, I have bought this bonnet. I do not think it is very pretty; but I thought I might as well buy it as not. I shall pull it to pieces as soon as I get home, and see if I can make it up any better.

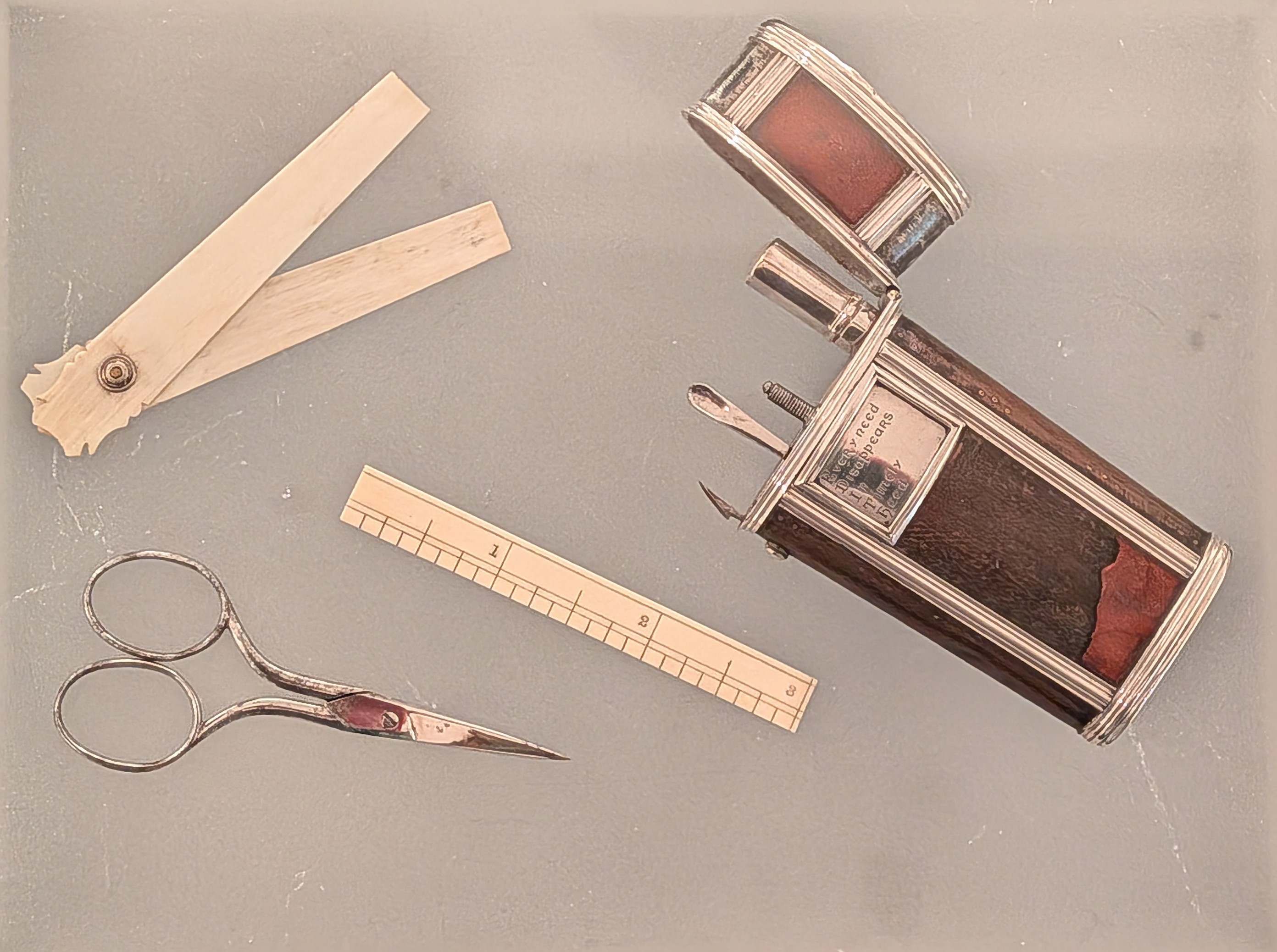

Serious difficulties faced women in trade in Austen’s time due to discrimination and a lack of legal rights, nevertheless many women did create and lead successful businesses. There are examples of women succeeding in fields such as construction, but the textile and clothing trades were particularly accessible. Some dressmakers and milliners worked from home for a little extra income. Most worked in shops for wages, often beginning as an apprentice. A few were able to set up their own. Specialist hat shops first appeared in the later 18th century. A milliner would also supply fabrics and trimmings, and items like fans and gloves. Most women made their own caps for indoor wear, but would buy hats, turbans and bonnets for outdoors and sometimes trim or alter them, like Lydia Bennet.

Mary Scoby Fielder was a successful and resilient Hampshire milliner. She was baptised Mary Elliot in 1756, in Wherwell, near Andover. In 1776, aged 21, she married 22-year-old Philip Scoby. Philip leased a property on the High Street, Winchester, and they probably lived and worked there together. The Hampshire Directory, 1784, lists Mary as a milliner, and Philip as a hair-dresser/wig-maker. The couple had four children in four years. Mary continued to develop her business, taking on several apprentices between 1781 and 1784. Sadly, in 1785, Philip died leaving her a widow with young children.

A year later, Mary married Joseph Fielder, a haberdasher from London. The marriage certificate gives Mary’s age as 25, shaving a few years off. Not long after, Mary advertised John Adcock as a successor in her business. The newly-weds may have moved to London. Research revealed a baptism record for Joseph Elliot, son of Joseph and Mary Fielder, born on 27th of March, 1787, in Fleet Street.